Medieval Gospel Commentary, lost for 1500 years – now translated and online

The earliest Latin Commentary on the Gospels, lost for over

1500 years, has been rediscovered and made available in English for the

first time, thanks to research from the University of Birmingham.

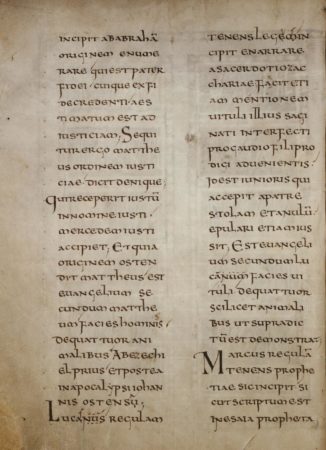

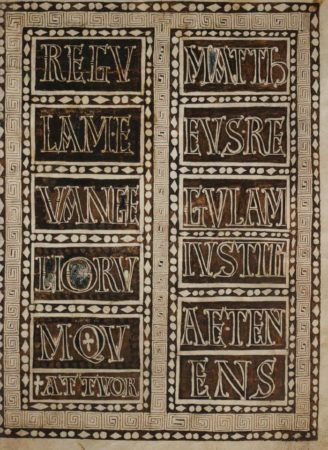

The extraordinary find, a work written by a bishop in North Italy, Fortunatianus of Aquileia, dates back to the middle of the fourth century. The biblical text of the manuscript is of particular significance, as it predates the standard Latin version known as the Vulgate and provides new evidence about the earliest form of the Gospels in Latin, shedding new light on the early Church.

Despite references to it in other ancient works, no copy was known to survive until a researcher from the University of Salzburg identified the commentary in an anonymous manuscript copied around the year 800 and held in Cologne Cathedral Library.

Hugh Houghton, of the University of Birmingham’s Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing (ITSEE), has been collaborating with Dr Lukas Dorfbauer, who discovered the manuscript in 2012, to produce an English translation in conjunction with the first-ever edition of this Latin text, which was published this week.

“Most of the works which survive from the earliest period of Latin Christianity are by later,” said Dr. Houghton, “more famous authors such as St Jerome, St Ambrose or St Augustine and have attained the status of classics. To discover a work which predates these well-known writers is an extraordinary find.

‘One of my contributions was to compare the biblical quotations in the Cologne manuscript with our databases here in Birmingham. Parallels with texts circulating in north Italy in the middle of the fourth century offer a perfect fit with the context of Fortunatianus.

‘Astonishingly, despite being copied four centuries after the last reference to his gospel commentary, this manuscript seems to preserve the original form of Fortunatianus’ ground-breaking work.’

The commentary is a substantial piece of writing, around one hundred pages long, which treats the Gospel according to Matthew in great detail and also covers sections from the Gospels according to Luke and John in 160 separate chapters.

The identification of the lost manuscript has also allowed the researchers to identify other, shorter pieces as the work of Fortunatianus. Previously these works had been assigned to other ancient authors, such as Chromatius, a later Bishop of Aquileia, or Hilary of Poitiers but are now proven to be extracts from Fortunatianus. Existing textbooks about the early reception of the Gospels will need to be revised to take account of this major find, which also contains important new material for liturgical studies and other aspects of early Christianity.

“Such a discovery is of considerable significance to our understanding of the development of Latin biblical interpretation, which went on to play such an important part in the development of Western thought and literature,” Dr Houghton added. “In this substantial commentary, Fortunatianus is reliant on even earlier writings which formed the link between Greek and Latin Christianity.

“This sheds new light on the way the Gospels were read and understood in the early Church, in particular the symbolic reading of the text known as ‘allegorical exegesis’. There are also moments of insight into the lives of fourth-century Italian Christians, as when the bishop uses a walnut as an image of the four Gospels or holds up a Roman coin as a symbol of the Trinity.’

The English translation, produced as part of the COMPAUL project funded by the European Research Council, is available online as a free, open-access download.